Final Sentence

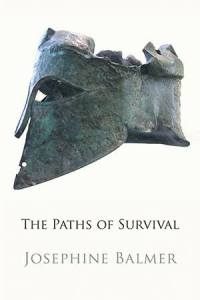

It is always a hugely exciting time when the hard work of several years is distilled into a written text. For this celebratory post on the publication of The Paths of Survival, as in the book, I’d like to begin at the end with a tattered piece of papyrus in the collection of an Oxford University library. Oxyrhynchus Papyrus 2256 contains nearly 90 scraps of papyrus. Of these, number 55 constitutes four, barely legible half-lines of Aeschylus’ lost play Myrmidons. Part of its text could read ‘kata skoton’ or ‘into darkness’ – a snatch, maybe, of the lover’s lament Achilles murmurs over Patroclus’ dead body. Here is the homoerotic passion which later rendered Myrmidons such a difficult and controversial work, probably sealing its demise (and a link, too, to the copy my fictional scribe is making, centuries earlier, in ‘Blot’ and then its disposal on the rubbish piles of Oxyrynchus in ‘The Pagan’s Tip’) .

It is, of course, heart-breaking that, along with a handful or so of similar fragments, this is all we have left of Aeschylus’ tragic masterpiece. It is also a warning that our own cultures might be far more fragile than we think. Yet in each small miracle of survival, there is always something to celebrate. For somehow, by judgement or by error but mostly through happenstance, something of the written text, of literary culture, however damaged, however minuscule, has managed to escape all those centuries of ignorance, war, persecution and destruction. Like the lined faces of the old, each crease and blemish tells a unique story of experience and endurance. Proof that words can – and do – thrive where all else is lost.

Final Sentence

(Sackler Library, Oxford, Present Day)

Still I am drawn to it like breath to glass.

That ache of absence, wrench of nothingness,

stark lacunae we all must someday face.

I imagine its letters freshly seared;

a scribe sighing over ebbing taper,

impatient to earn night’s coming pleasures

as light seeped out of Alexandria.

But in these hushed corners of Oxford

Library afternoons, milky with dust,

the air is weighted down by accruing loss

and this displaced scrap of frayed papyrus

whose mutilated words can just be read,

one final, half-sentence: Into darkness…

Prophetic. Patient. Hanging by a thread.

Josephine Balmer

The Paths of Survival is published by Shearsman. You can order a copy here or here.

Scribes are the unsung heroes of the survival of any classical work; without them there would be no written papyrus texts and codices, and hence no fragments of drama or poetry. We know that scribes often worked from ‘scriptoriums’, maybe booths or workshops in city marketplaces where customers might request a work to be copied for their private libraries.

Scribes are the unsung heroes of the survival of any classical work; without them there would be no written papyrus texts and codices, and hence no fragments of drama or poetry. We know that scribes often worked from ‘scriptoriums’, maybe booths or workshops in city marketplaces where customers might request a work to be copied for their private libraries.

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century

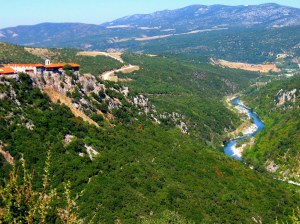

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century  Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post

Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post  Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews.

Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews.