Things We Leave Behind: Selected Poems

Today sees the publication of Things We Leave Behind: Selected Poems, the culmination of twenty-one years’ work as a published poet (and more than forty as a classical translator). Edited by Paschalis Nikolaou, the volume includes poems from all five of my collections, from Chasing Catullus: poems, translations and transgression in 2004 (Bloodaxe) to 2022’s Ghost Passage (Shearsman), as well as some new poems from a current work-in-progress. All of these works have explored the relationship of the present to the distant past, the personal to the universal, translation to original.

It is difficult to pick one poem which sums up their trajectory but ‘Star’ from 2017’s Letting Go comes close. One of the final sonnets in a sequence written in response to my mother’s sudden death, it is concerned with reconciliation and acceptance, with the consolation that can be found in a beloved landscape, as well as the echoes that resonate down through the centuries to bring us comfort – ‘the sound of words you can’t say’ – here quoting lines from Sappho fragments 104b & a in lines 10-14, based on my own previous translations. It is accompanied below by one of the images created by Alistair Common for our joint exhibition of poetry and photography at the University of Exeter in November 2024.

Star

So we come full circle to falling dusk.

Above Priest’s Cove, the sky is darkening

through Brisons rocks, evening hesitating

between clouds and sea, cautious, on the cusp.

A shard of moon slips through, blurred with regret,

fresh votive to this place, our penitence

for the lost: parents, old friends and the house

we mourned as if a lover rashly left.

But the day has gone, its turning point passed.

Now the most beautiful of all the stars –

the evening star, shepherd star, Hesperus –

gathers all that light-tinged dawn has scattered;

it guides the fishing boats, herds in sailors,

sends daughters running home to their mothers.

Josephine Balmer

Image © Alistair Common

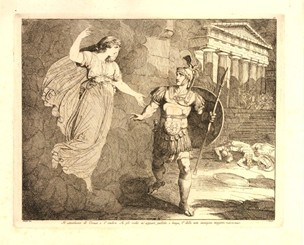

In 60 CE, nearly twenty years after the Roman emperor Claudius had annexed Britain, British tribes led by the Iceni Queen Boudica revolted against their Roman conquerors. In his account of the rebellion, the Roman historian Tacitus describes how the British first turned their attention to the city of Camulodunum, modern Colchester, razing it to the ground, before marching on Londinium or London.

In 60 CE, nearly twenty years after the Roman emperor Claudius had annexed Britain, British tribes led by the Iceni Queen Boudica revolted against their Roman conquerors. In his account of the rebellion, the Roman historian Tacitus describes how the British first turned their attention to the city of Camulodunum, modern Colchester, razing it to the ground, before marching on Londinium or London. The following poem, first published in the New Statesman earlier this year (18th April) is written in the voice of Suetonius Paulinus. It follows firstly Greek historian Cassius Dio’s description (63) of the portents that preceded Boudica’s attack and then Tacitus’s own account in his Annals (14.33) which pinpoints the human cost of Suetonius’s decision:

The following poem, first published in the New Statesman earlier this year (18th April) is written in the voice of Suetonius Paulinus. It follows firstly Greek historian Cassius Dio’s description (63) of the portents that preceded Boudica’s attack and then Tacitus’s own account in his Annals (14.33) which pinpoints the human cost of Suetonius’s decision:

Tomorrow marks the eighth anniversary of my mother’s death. As anyone who has suffered a similar loss will know, this time has passed so slowly and at the same time so quickly too. Last year I published a sequence of thirty sonnets,

Tomorrow marks the eighth anniversary of my mother’s death. As anyone who has suffered a similar loss will know, this time has passed so slowly and at the same time so quickly too. Last year I published a sequence of thirty sonnets,

As a translator, revisiting a text or series of texts you first worked on many years ago is always a fascinating – and daunting – task. This week Bloodaxe Books publish a new, revised edition of my

As a translator, revisiting a text or series of texts you first worked on many years ago is always a fascinating – and daunting – task. This week Bloodaxe Books publish a new, revised edition of my  The fragment’s second stanza is far more incomplete but nevertheless contains some startling images. In line 6 of the fragment the words ep’akras, or literally ‘on the edges’, could refer to a Greek expression for ‘on tiptoes’. The following line appears to have an equally arresting reference to chion, in Homer used of fallen snow. This could evoke the figure of Kairos or ‘Opportunity’, the concept of acting at the correct time or seizing the day, which in Greek art and mythology was often portrayed as a young man running on tiptoes. But ep’akras was also used of being ‘on the edge’ of a changing season, particularly spring, which chimed with the later mention of (perhaps melting) snow. In addition, the verb which Obbink reads as ebas, or ‘you went’ echoes the eba (‘she went’) used of Helen’s desertion of Paris in fragment 16. And so I added in some conjectures here to include the image of a lover leaving like fleeting snow in the spring:

The fragment’s second stanza is far more incomplete but nevertheless contains some startling images. In line 6 of the fragment the words ep’akras, or literally ‘on the edges’, could refer to a Greek expression for ‘on tiptoes’. The following line appears to have an equally arresting reference to chion, in Homer used of fallen snow. This could evoke the figure of Kairos or ‘Opportunity’, the concept of acting at the correct time or seizing the day, which in Greek art and mythology was often portrayed as a young man running on tiptoes. But ep’akras was also used of being ‘on the edge’ of a changing season, particularly spring, which chimed with the later mention of (perhaps melting) snow. In addition, the verb which Obbink reads as ebas, or ‘you went’ echoes the eba (‘she went’) used of Helen’s desertion of Paris in fragment 16. And so I added in some conjectures here to include the image of a lover leaving like fleeting snow in the spring: