Translating Fragments III: Aeschylus’s Myrmidons

As my last two blogs in this series have shown, the translation of ancient fragments has long been problematic. Should they be elongated to provide a contextual framework? Or should they be left incomplete, a mysterious shard from a long-vanished world? Aeschylus fragment 134 is particularly challenging. It is attributed to the tragedian’s lost masterpiece, Myrmidons, which dramatised the Greek hero Achilles’s withdrawal from the Trojan War after a disagreement with his war-leader Agamemnon, with tragic consequences; Achilles’s lover and fellow warrior, Patroclus, fights in his place only to be slain by the Trojan prince Hector. The damaged text of the two-line fragment appears to read as follows: ‘…[our] gilded horse-cockerel [mastheads], crafted by careful labour, are dripping [like wax?]…’

As my last two blogs in this series have shown, the translation of ancient fragments has long been problematic. Should they be elongated to provide a contextual framework? Or should they be left incomplete, a mysterious shard from a long-vanished world? Aeschylus fragment 134 is particularly challenging. It is attributed to the tragedian’s lost masterpiece, Myrmidons, which dramatised the Greek hero Achilles’s withdrawal from the Trojan War after a disagreement with his war-leader Agamemnon, with tragic consequences; Achilles’s lover and fellow warrior, Patroclus, fights in his place only to be slain by the Trojan prince Hector. The damaged text of the two-line fragment appears to read as follows: ‘…[our] gilded horse-cockerel [mastheads], crafted by careful labour, are dripping [like wax?]…’

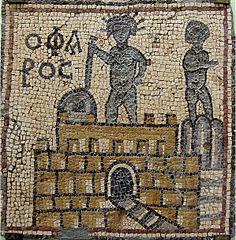

Even shortly after Aeschylus’s death, the comic playwright Aristophanes was quoting the fragment as an example of Aeschylus’s incomprehensible verse – and in fact this is how the fragment survived. In particular, Aristophanes joked about the hippalektruon or ‘horse-cockerel’ referred to by the fragment, a beast from Greek mythology with a horse’s head and cock’s tail. This, as Aristophanes has Aeschylus himself explain in Frogs (l. 934), apparently refers to the wooden masthead of a Greek warship, presumably burnt when the Trojans took advantage of Achilles’ absence from the battlefield – as the subsequent reference to the verb stazei or ‘drip’seems to attest.

Clearly, even to the ancients, these were difficult and impenetrable lines. My version, originally published in the Transitions issue of Modern Poetry in Translation, but now updated here (and included in my collection The Paths of Survival), looks to a radical way of approaching the fragment’s translation, by embedding the piece within the poetic narrative of a longer piece. In the form of Seamus Heaney’s ‘sonnet and a half’, this offers a means to enact not just the fragment’s literal meaning but also the complexity of its reception, even within the ancient world. Through a monologue by a fictional historical character, a third century BC Alexandrian boatman who shares his name, Charon, with the ferryman of the dead in Hades, the poem describes a crucial moment in the transmission – and loss – of the text. Here the Alexandrians, eager to built up texts for their new Library by decreeing that all works found on boats in their harbour would be borrowed for copying, decide to retain the original of Aeschylus’s work, breaking all their previous promises. In this way, the confusion (and also wonder) of the fictional characters reflects our own. In addition, the alluring opaqueness of the fragment can be preserved, alongside its integrity, as well as a narrative context for modern readers.

Charon’s Roll

(Alexandria, c.230 BC)

The lads tease me, call me Charon. I row

out to anchored ships at night, take my tax

as ferryman, not of pennies but texts,

as our Law decrees, seizing plays, poems

for transcribing in our new Musaeum,

swearing to return all works I ‘borrow’.

Last week I took some rolls of Aeschylus

to Callimachus, our famed Librarian:

gilded horse-cockerels, we read, perplexed,

crafted mastheads, now melting, drip by drip,

in the corrosive fires of burning ships…

We joked how they must drink, these Athenians.

Callimachus did not laugh. It was fate

he said: here were the Greek prows at Troy, torched

as Achilles sulked. Myrmidons. Lines thought

so prized now that he would not give them back.

We all groaned, aghast. Yet more horse-cocks.

And then I glanced at Callimachus’s face

caught in a shifting taper as he talked –

like a city put to flame, molten wax

about to twist the world into new shapes.

As we have seen with

As we have seen with

A year or so ago, while on holiday in the Derbyshire Peak District, my husband bought me a pair of blue john earrings from one of the many jewellers in the village of Castleton. Castleton is extremely proud of its blue john, and is the only place in the country where the stone occurs, so we were also presented with a leaflet about its history. This claimed blue john had first been mined by the Romans and even mentioned by the ancient historians Pliny and Tacitus. These, we read, record how the first century AD Roman writer and sensualist, Petronius, author of the Satyricon, one of the earliest novels in literature, had owned a precious chalice made of the Derbyshire stone.

A year or so ago, while on holiday in the Derbyshire Peak District, my husband bought me a pair of blue john earrings from one of the many jewellers in the village of Castleton. Castleton is extremely proud of its blue john, and is the only place in the country where the stone occurs, so we were also presented with a leaflet about its history. This claimed blue john had first been mined by the Romans and even mentioned by the ancient historians Pliny and Tacitus. These, we read, record how the first century AD Roman writer and sensualist, Petronius, author of the Satyricon, one of the earliest novels in literature, had owned a precious chalice made of the Derbyshire stone. Intrigued, I tracked down the passages in both authors (Tacitus Annals, 17.18-19 & Pliny Natural History 37.7) who both recounted how, before comitting suicide after an accusation of treason, Petronius had destroyed his valuable cup so that the emperor Nero could not subsequently possess it. Of course, as it so often the case with anecdotal evidence, scholarship was more sceptical that Petronius’s cup was made of blue john; for while the Romans undoubtedly mined British metals and stone – some of the resources that first drew them to the island – Pliny’s description of the chalice as ‘myrrhinam’ has been taken to refer to an imported Chinese porcelain, hence its high value. But for the purposes of poetry rather than scholarship, this connection between a sophisticated, urbane writer and courtier at the very centre of the Roman empire and a tiny Peakland outpost on its northerly British edge seemed too fascinating to eschew, as the following poem explores. First published in

Intrigued, I tracked down the passages in both authors (Tacitus Annals, 17.18-19 & Pliny Natural History 37.7) who both recounted how, before comitting suicide after an accusation of treason, Petronius had destroyed his valuable cup so that the emperor Nero could not subsequently possess it. Of course, as it so often the case with anecdotal evidence, scholarship was more sceptical that Petronius’s cup was made of blue john; for while the Romans undoubtedly mined British metals and stone – some of the resources that first drew them to the island – Pliny’s description of the chalice as ‘myrrhinam’ has been taken to refer to an imported Chinese porcelain, hence its high value. But for the purposes of poetry rather than scholarship, this connection between a sophisticated, urbane writer and courtier at the very centre of the Roman empire and a tiny Peakland outpost on its northerly British edge seemed too fascinating to eschew, as the following poem explores. First published in In his Letters (3.16), Pliny tells the story of the first century AD Roman matron Arria, whose husband and young son both fell gravely ill at the same time. When her son died, Pliny records, Arria did not tell her husband, Caecina Paetus, concerned that the news would be detrimental to his own recovery, instead mourning the loss of her son alone. But the real story comes some years later when Paetus took part in a failed revolt against the emperor Claudius. Apparently he then hesitated before taking the honourable way out, suicide. Arria was not so cowardly. As Pliny recounts, she plunged the sword in her own breast first, reassuring her wavering husband that it would be painless – words that later seem to have become proverbial in Latin. For Pliny, Arria is a dutiful Roman wife, heroically standing by her husband no matter what. The following poem, first published in

In his Letters (3.16), Pliny tells the story of the first century AD Roman matron Arria, whose husband and young son both fell gravely ill at the same time. When her son died, Pliny records, Arria did not tell her husband, Caecina Paetus, concerned that the news would be detrimental to his own recovery, instead mourning the loss of her son alone. But the real story comes some years later when Paetus took part in a failed revolt against the emperor Claudius. Apparently he then hesitated before taking the honourable way out, suicide. Arria was not so cowardly. As Pliny recounts, she plunged the sword in her own breast first, reassuring her wavering husband that it would be painless – words that later seem to have become proverbial in Latin. For Pliny, Arria is a dutiful Roman wife, heroically standing by her husband no matter what. The following poem, first published in  Two years before his death in 217AD (see my previous entry), the Roman emperor Caracalla had perpetrated an act of extreme savagery against the citizens of ancient Alexandria in revenge for their satires about him. In particular, the Alexandrians were said to be making gibes about the fact that Caracalla had murdered his brother – and then co-emperor – Geta in front of their own mother whom, it was rumoured, he then planned to marry. Caracalla’s revenge was not only brutal but, according to surviving accounts by ancient historians Dio Cassius and Herodian, reveals many chilling similarities with the actions of more modern despots. For instance, Caracalla’s duplicity and delight in tricking the Alexandrians into watching the massacre of all of the city’s young men, his lack of remorse at his bloodthirsty actions, his pretensions to culture, and his subsequent ‘walling-in’ of Alexandrian neighbourhoods, like an ancient version of the Warsaw Ghetto, all seem terrifyingly recognizable today. The poem appears in my collection,

Two years before his death in 217AD (see my previous entry), the Roman emperor Caracalla had perpetrated an act of extreme savagery against the citizens of ancient Alexandria in revenge for their satires about him. In particular, the Alexandrians were said to be making gibes about the fact that Caracalla had murdered his brother – and then co-emperor – Geta in front of their own mother whom, it was rumoured, he then planned to marry. Caracalla’s revenge was not only brutal but, according to surviving accounts by ancient historians Dio Cassius and Herodian, reveals many chilling similarities with the actions of more modern despots. For instance, Caracalla’s duplicity and delight in tricking the Alexandrians into watching the massacre of all of the city’s young men, his lack of remorse at his bloodthirsty actions, his pretensions to culture, and his subsequent ‘walling-in’ of Alexandrian neighbourhoods, like an ancient version of the Warsaw Ghetto, all seem terrifyingly recognizable today. The poem appears in my collection,