The Monastery’s Treasure

A tiny yet passionate fragment of Aeschylus’s lost drama Myrmidons is discovered in a surprising place…

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century Lexicon of Photius was discovered at the remote Greek Orthodox Monastery of Zavorda in Macedonia, northern Greece (you can find an account of this by Roger Pearse here). This edition included some pages that were not available in other known editions of the Lexicon, all based on the Codex Galeanus, a 12th century parchment ms. of 149 leaves. Although the Zavorda manuscript is later than the Codex Galeanus, dating from the 13th-14th century, it is the only complete surviving manuscript of the text, containing additional pages and entries absent from other editions, including words beginning with alpha (άβ to άγ).

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century Lexicon of Photius was discovered at the remote Greek Orthodox Monastery of Zavorda in Macedonia, northern Greece (you can find an account of this by Roger Pearse here). This edition included some pages that were not available in other known editions of the Lexicon, all based on the Codex Galeanus, a 12th century parchment ms. of 149 leaves. Although the Zavorda manuscript is later than the Codex Galeanus, dating from the 13th-14th century, it is the only complete surviving manuscript of the text, containing additional pages and entries absent from other editions, including words beginning with alpha (άβ to άγ).

I was taken with the fact that these new extra pages include the Greek word abdeluktos which, as previously discussed, Photius tells us means ‘without stain’ or ‘absolved of blame’. Unlike other, later sources, he also notes that it originates in a line from Aeschylus’s lost play Myrmidons, almost certainly as the grieving hero Achilles embraces the corpse of his slain lover Patroclus, exclaiming that such an act is not an abomination ‘because I love him’.

Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post here. As well as marvelling at the tiny miracles and random happenstance at the heart of such textual survivals, I also wondered how the monks would have felt had they known that, for centuries, they had been custodians of evidence of such a passionate, later forbidden love.

Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post here. As well as marvelling at the tiny miracles and random happenstance at the heart of such textual survivals, I also wondered how the monks would have felt had they known that, for centuries, they had been custodians of evidence of such a passionate, later forbidden love.

The following poem, ‘Trespass’, from my collection, The Paths of Survival, explores that conundrum through the voice of an imaginary monk, forming a companion piece to Photius’s own voice in the poem ‘Gloss’.

Trespass

(Monastery of Zavorda, Macedonia, 1959)

From the crag we watched as he drew

near, creeping closer like a contagion.

‘My son, we have been expecting you,’

our unsmiling abbot said in welcome.

From the cadence of his voice we knew

he was not talking of days or decades

but the dry passage of our centuries.

For weeks our guest rifled the libraries,

their rare treasures piled around him –

like a child’s toys or stored-up treats.

Now our abbot did not eat or sleep.

We saw the apprehension in his face

as if some half-recalled, splintered dream

had returned, long dreaded, to haunt him,

a fear he could barely form or elucidate.

Our guest found all he had come to seek:

a tattered codex wrapped round in rags

like some precious shard of brittle glass.

He put on his hat and coat, his work done,

a few more words for his literary canon:

Abdeluktos philo. Absolved because I loved him…

Anathema. The taint of unconstrained sin –

a snatch of Aeschylus’s foul Myrmidons.

In its shadow we had held sacred homily,

called our brethren to vespers, benediction.

Now it was unleashed again, this heresy

we had guarded here without knowing

for so long. Unspeakable acts. Trespass.

We waited as he faded, a blur in the dark,

disappearing back into fold of river pass.

Josephine Balmer

.

Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews.

Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews. Eight hundred and twelve years ago to the day, on April 8th 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, the siege of Constantinople began. What distinguishes this Crusade is that, rather than a conflict between Christian and Muslim Arabs, it pitted Christian against Christian, as mutinous Crusader forces from the western or Latin church turned their attention on the eastern city of Constantinople, drawn, in part, by the booty to be looted from its famous riches.

Eight hundred and twelve years ago to the day, on April 8th 1204, during the Fourth Crusade, the siege of Constantinople began. What distinguishes this Crusade is that, rather than a conflict between Christian and Muslim Arabs, it pitted Christian against Christian, as mutinous Crusader forces from the western or Latin church turned their attention on the eastern city of Constantinople, drawn, in part, by the booty to be looted from its famous riches. Today is Mothering Sunday in the UK. It would also have been my mother’s 82nd birthday. It’s a difficult day for all who have lost a beloved parent – or child – but the following poem, from my forthcoming sonnet sequence,

Today is Mothering Sunday in the UK. It would also have been my mother’s 82nd birthday. It’s a difficult day for all who have lost a beloved parent – or child – but the following poem, from my forthcoming sonnet sequence,  Odysseus’s description seemed to chime with the view from a seat on the coastal foot path near my mother’s childhood house in Marazion, west Cornwall. As a girl, my mother often sat on the seat with her own mother or her aunt on the way to church at Perranuthnoe on Sunday evenings. Later I sat with her there many times, looking out over St Michael’s Mount and its Bay, chatting about family or the wildflowers we saw in the verges. I sat there again last April with my husband Paul just as the blossom was coming out along the hedgerows:

Odysseus’s description seemed to chime with the view from a seat on the coastal foot path near my mother’s childhood house in Marazion, west Cornwall. As a girl, my mother often sat on the seat with her own mother or her aunt on the way to church at Perranuthnoe on Sunday evenings. Later I sat with her there many times, looking out over St Michael’s Mount and its Bay, chatting about family or the wildflowers we saw in the verges. I sat there again last April with my husband Paul just as the blossom was coming out along the hedgerows:

Nigel Farage might have been concerned about Romanians moving in next door but, as an inscription from Roman Colchester reveals, eastern European immigrants have been part of the British landscape since the first century A.D.

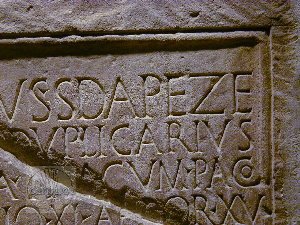

Nigel Farage might have been concerned about Romanians moving in next door but, as an inscription from Roman Colchester reveals, eastern European immigrants have been part of the British landscape since the first century A.D. In his funerary sculpture, Longinus is depicted on his horse with his cavalry chain mail tunic and small round shield, brandishing his spear while a defeated British tribesman cowers beneath his horse’s hooves. The damaged text of the tomb’s inscription translates literally as follows: Longinus, Sdapeze s[on of] Matygus, duplicarius, of the 1st cavalry squadron of Thracians from the district of Sardica, aged 40, with 15 years service, lies here. His heirs erected this under his will.

In his funerary sculpture, Longinus is depicted on his horse with his cavalry chain mail tunic and small round shield, brandishing his spear while a defeated British tribesman cowers beneath his horse’s hooves. The damaged text of the tomb’s inscription translates literally as follows: Longinus, Sdapeze s[on of] Matygus, duplicarius, of the 1st cavalry squadron of Thracians from the district of Sardica, aged 40, with 15 years service, lies here. His heirs erected this under his will.