Thumbs-Up: A Woman Gladiator in Roman London?

In 1996, a 2nd-3rd century CE Roman grave was discovered in Southwark London containing some fascinating grave goods of eight clay lamps, one of which shows a fallen gladiator. Three more depict Anubis, the Egyptian god of the dead in the Isis cult, who accompanied souls on their journey to the underworld and was often associated with gladiators (all are now on display in the Museum of London). So was this the grave of a professional gladiator? Possibly. But there was one further piece of the puzzle. This was the grave of a woman.

Female gladiators are known from imperial Rome and great excitement followed, particularly in the press, about the idea of one being buried in London. Archaeologists, as they are apt, were rather more wary. Some suggested that the woman could have been simply a devotee of the Games (Juvenal’s Satires reveal that many Roman women followed them avidly). Others concluded that the grave goods suggested a more general belief in the afterlife and the possibility of resurrection, represented by gladiatorial conquests and, in particular, their missio or respite after being defeated: the thumbs-up. In my poem from Ghost Passage, inspired by the grave, I wanted to admit to both possibilities. To keep things open, as poetry can do perhaps more easily than scholarship. The eerily atmospheric remains of London’s Roman Amphitheatre, hidden away beneath the Guildhall in the City of London, also provided inspiration.

Thumbs Up

Gladiator grave lamps, Southwark, London, 220 CE

Even as a girl I was besotted, mesmerised.

For my tenth birthday my father sent me

to the Games. He told me we were Isaics,

Syrians, who honoured the boundaries

between passing worlds, this and the next.

We did not come, he warned, to watch men die

but to rehearse our own, approaching deaths.

I learnt that we all stare through the cracks

of the Underworld. Gladiators report back.

That day I understood how it feels to breathe

by common lungs; how our fear pulses

through a shared vein, a spider’s thread spun

across from warrior to warrior to spectator.

Time passed. Once, somewhere, I gave birth;

my first kill was on account. The rest

without remorse. Thrust by thrust, lunge

by lunge, roar by roar, I matched the men

in battle lust. Now my own death is here.

I light its rusted path with lamps for Anubis

keeper of secrets, weigher of souls. I wait

at his trembling threshold to beg for missio

and redemption. Thumbs up. As I hesitate

in that closing light, I hear the hushed slow

hum of blood. And then walk with courage

from arena into gore-sluiced darkness.

In 60 CE, nearly twenty years after the Roman emperor Claudius had annexed Britain, British tribes led by the Iceni Queen Boudica revolted against their Roman conquerors. In his account of the rebellion, the Roman historian Tacitus describes how the British first turned their attention to the city of Camulodunum, modern Colchester, razing it to the ground, before marching on Londinium or London.

In 60 CE, nearly twenty years after the Roman emperor Claudius had annexed Britain, British tribes led by the Iceni Queen Boudica revolted against their Roman conquerors. In his account of the rebellion, the Roman historian Tacitus describes how the British first turned their attention to the city of Camulodunum, modern Colchester, razing it to the ground, before marching on Londinium or London. The following poem, first published in the New Statesman earlier this year (18th April) is written in the voice of Suetonius Paulinus. It follows firstly Greek historian Cassius Dio’s description (63) of the portents that preceded Boudica’s attack and then Tacitus’s own account in his Annals (14.33) which pinpoints the human cost of Suetonius’s decision:

The following poem, first published in the New Statesman earlier this year (18th April) is written in the voice of Suetonius Paulinus. It follows firstly Greek historian Cassius Dio’s description (63) of the portents that preceded Boudica’s attack and then Tacitus’s own account in his Annals (14.33) which pinpoints the human cost of Suetonius’s decision:

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century

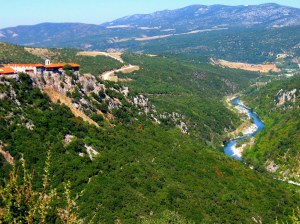

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century  Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post

Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post

A year or so ago, while on holiday in the Derbyshire Peak District, my husband bought me a pair of blue john earrings from one of the many jewellers in the village of Castleton. Castleton is extremely proud of its blue john, and is the only place in the country where the stone occurs, so we were also presented with a leaflet about its history. This claimed blue john had first been mined by the Romans and even mentioned by the ancient historians Pliny and Tacitus. These, we read, record how the first century AD Roman writer and sensualist, Petronius, author of the Satyricon, one of the earliest novels in literature, had owned a precious chalice made of the Derbyshire stone.

A year or so ago, while on holiday in the Derbyshire Peak District, my husband bought me a pair of blue john earrings from one of the many jewellers in the village of Castleton. Castleton is extremely proud of its blue john, and is the only place in the country where the stone occurs, so we were also presented with a leaflet about its history. This claimed blue john had first been mined by the Romans and even mentioned by the ancient historians Pliny and Tacitus. These, we read, record how the first century AD Roman writer and sensualist, Petronius, author of the Satyricon, one of the earliest novels in literature, had owned a precious chalice made of the Derbyshire stone. Intrigued, I tracked down the passages in both authors (Tacitus Annals, 17.18-19 & Pliny Natural History 37.7) who both recounted how, before comitting suicide after an accusation of treason, Petronius had destroyed his valuable cup so that the emperor Nero could not subsequently possess it. Of course, as it so often the case with anecdotal evidence, scholarship was more sceptical that Petronius’s cup was made of blue john; for while the Romans undoubtedly mined British metals and stone – some of the resources that first drew them to the island – Pliny’s description of the chalice as ‘myrrhinam’ has been taken to refer to an imported Chinese porcelain, hence its high value. But for the purposes of poetry rather than scholarship, this connection between a sophisticated, urbane writer and courtier at the very centre of the Roman empire and a tiny Peakland outpost on its northerly British edge seemed too fascinating to eschew, as the following poem explores. First published in

Intrigued, I tracked down the passages in both authors (Tacitus Annals, 17.18-19 & Pliny Natural History 37.7) who both recounted how, before comitting suicide after an accusation of treason, Petronius had destroyed his valuable cup so that the emperor Nero could not subsequently possess it. Of course, as it so often the case with anecdotal evidence, scholarship was more sceptical that Petronius’s cup was made of blue john; for while the Romans undoubtedly mined British metals and stone – some of the resources that first drew them to the island – Pliny’s description of the chalice as ‘myrrhinam’ has been taken to refer to an imported Chinese porcelain, hence its high value. But for the purposes of poetry rather than scholarship, this connection between a sophisticated, urbane writer and courtier at the very centre of the Roman empire and a tiny Peakland outpost on its northerly British edge seemed too fascinating to eschew, as the following poem explores. First published in In his Letters (3.16), Pliny tells the story of the first century AD Roman matron Arria, whose husband and young son both fell gravely ill at the same time. When her son died, Pliny records, Arria did not tell her husband, Caecina Paetus, concerned that the news would be detrimental to his own recovery, instead mourning the loss of her son alone. But the real story comes some years later when Paetus took part in a failed revolt against the emperor Claudius. Apparently he then hesitated before taking the honourable way out, suicide. Arria was not so cowardly. As Pliny recounts, she plunged the sword in her own breast first, reassuring her wavering husband that it would be painless – words that later seem to have become proverbial in Latin. For Pliny, Arria is a dutiful Roman wife, heroically standing by her husband no matter what. The following poem, first published in

In his Letters (3.16), Pliny tells the story of the first century AD Roman matron Arria, whose husband and young son both fell gravely ill at the same time. When her son died, Pliny records, Arria did not tell her husband, Caecina Paetus, concerned that the news would be detrimental to his own recovery, instead mourning the loss of her son alone. But the real story comes some years later when Paetus took part in a failed revolt against the emperor Claudius. Apparently he then hesitated before taking the honourable way out, suicide. Arria was not so cowardly. As Pliny recounts, she plunged the sword in her own breast first, reassuring her wavering husband that it would be painless – words that later seem to have become proverbial in Latin. For Pliny, Arria is a dutiful Roman wife, heroically standing by her husband no matter what. The following poem, first published in