The Pagan’s Tip

A family in fourth century CE Oxyrhynchus decides it is time to dispose of their library of classical, pre-Christian texts…

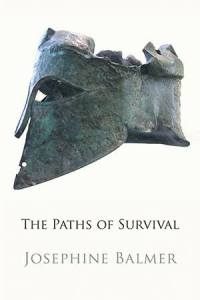

In my last post, a fictional Alexandrian scribe copied lines of Aeschylus’ Myrmidons for a cash-rich family from Oxyrhynchus. Here, in another poem from my forthcoming collection, The Paths of Survival, we move on in time another two centuries to find his customer’s descendants deciding that, in a Christian empire, it is time to make a gesture.

In my last post, a fictional Alexandrian scribe copied lines of Aeschylus’ Myrmidons for a cash-rich family from Oxyrhynchus. Here, in another poem from my forthcoming collection, The Paths of Survival, we move on in time another two centuries to find his customer’s descendants deciding that, in a Christian empire, it is time to make a gesture.

In particular, they feel, it would be politic to dump the works in their treasured family library on the town rubbish tip – including the copies of Aeschylus’ tragedies our cantankerous scribe had worked so hard to produce for them. Here, of course, the papyri will later be excavated in tattered strips by late nineteenth and early twentieth century archaeologists, beginning the painstaking process of piecing what little might remain of those texts back together…:

In particular, they feel, it would be politic to dump the works in their treasured family library on the town rubbish tip – including the copies of Aeschylus’ tragedies our cantankerous scribe had worked so hard to produce for them. Here, of course, the papyri will later be excavated in tattered strips by late nineteenth and early twentieth century archaeologists, beginning the painstaking process of piecing what little might remain of those texts back together…:

The Pagan’s Tip

(Oxyrhynchus, Upper Egypt, 370)

Today we sacrificed our last bull –

not easy with just the five of us.

Walking back with Kallas, my cousin,

we both agreed it was time to stop.

Now, we said, we are all Christians.

That night I gathered up the volumes

my family had prized over the years:

philosophy, poetry, the great dramas

of Aeschylus, epigrams of Palladas –

works our ancestor had bought home

in triumph from a trip to Alexandria.

Those pages hold our history like maps.

If I run my fingers over the covers,

their gold letters and tooled leather,

I can trace the twisted paths of our past.

This is who we were and what we are:

grammarians, clerks, petty bureaucrats.

On the shelf I replaced each space

with Paul’s Epistles, all the Gospels.

Ours I took out beyond the walls

among the flies and rotting waste,

left them there for the rats to soil

like any piece of discarded refuse.

Do the same, if you want my advice.

Josephine Balmer

The Paths of Survival will be published by Shearsman on April 7th.

Scribes are the unsung heroes of the survival of any classical work; without them there would be no written papyrus texts and codices, and hence no fragments of drama or poetry. We know that scribes often worked from ‘scriptoriums’, maybe booths or workshops in city marketplaces where customers might request a work to be copied for their private libraries.

Scribes are the unsung heroes of the survival of any classical work; without them there would be no written papyrus texts and codices, and hence no fragments of drama or poetry. We know that scribes often worked from ‘scriptoriums’, maybe booths or workshops in city marketplaces where customers might request a work to be copied for their private libraries.

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century

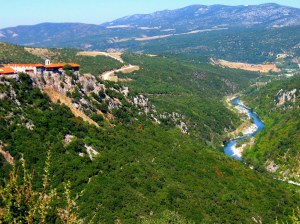

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century  Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post

Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post  Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews.

Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews.