The Librarians’ Power

This week is National Libraries Week, a celebration of the wonderful work libraries – and their librarians – do over and over again, day in, day out, offering us all free access to books, especially in these times of increasingly severe local authority budget cuts.

This week is National Libraries Week, a celebration of the wonderful work libraries – and their librarians – do over and over again, day in, day out, offering us all free access to books, especially in these times of increasingly severe local authority budget cuts.

From classical times onwards, this work has always been highly-valued and history resonates with the grief of the loss of such institutions. The story of the destruction of the first great library at Alexandria is told over and over again, if often by sources hostile to the alleged perpetrators. We learn of the accidental fire of Julius Caesar in 48 BCE, the supposed malicious damage of rioting Christian mobs in 391 CE or even the alleged burning of the last few remaining volumes in the city’s bathhouse furnaces by its Arab conqueror Amr ibn al-Asi in 642 (the last is almost certainly apocryphal). Whatever the cause, whatever the agenda of its chroniclers, this sense of horror at the loss of the written word reverberates through the centuries.

But such devastating, wholesale destruction is not confined to the classical or early medieval era. In 2003, during the Gulf War, the famed and ancient National Library of Baghdad was set on fire by a stray incendiary bomb, illustrating how the destruction of literary culture is, sadly, still relevant to us in the twenty-first century. And how we should never take our libraries for granted.

Apart from the National Library’s own important collections, such Arabic centers of learning have always been important in preserving classical literature over the centuries, particularly scientific works. And within such works of science, small snatches of more literary texts were often quoted – and so also saved. And again, in 2003, its determined and dedicated librarians battled to recover its precious, ancient books in the aftermath of the bomb.

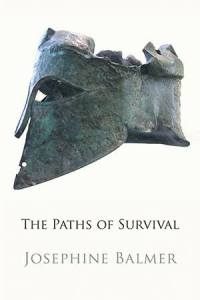

The following poem from The Paths of Survival was inspired by an article by Zainab Bahrani with photographs by Roger LeMoyne in the US journal Document (Spring/Summer 2013), and gives voices to those amazing Baghdad Librarians:

The Librarians’ Power

(The National Library, Baghdad, 2003)

We carried what we could to safety.

They seemed like something living:

fungus on an oak, the pleated folds

of open mushroom cup, organisms

that were once books, manuscripts,

now debris of ‘precision’ incendiary.

To conserve them we needed ice

not fire. In a ruined kitchen cellar

we found a freezer but no power;

we canvassed, coaxed, cajoled

until locals offered the sacrifice

of their one precious generator.

We were asked why we struggled

to save books while all around us

so many of our citizens were lost.

We could only say that, if not flesh,

here were dividing cells, bare blocks

of collective memory. Conscience.

The vast record of all our knowledge

and of our faith: an ancient Quran,

the House of Wisdom we had built;

the learning we alone had salvaged

and then protected for the Greeks –

Ptolemy’s Almagest, science, medicine.

Those lost worlds were retrieved

in the flash of forceps, lifting piece

on tiny piece, word on broken word.

Our own enduring, unshakeable belief

that in each newly-deciphered letter

a poem waited to be recovered.

Josephine Balmer

In my last

In my last  In particular, they feel, it would be politic to dump the works in their treasured family library on the town rubbish tip – including the copies of Aeschylus’ tragedies our cantankerous scribe had worked so hard to produce for them. Here, of course, the papyri will later be excavated in tattered strips by late nineteenth and early twentieth century archaeologists, beginning the painstaking process of piecing what little might remain of those texts back together…:

In particular, they feel, it would be politic to dump the works in their treasured family library on the town rubbish tip – including the copies of Aeschylus’ tragedies our cantankerous scribe had worked so hard to produce for them. Here, of course, the papyri will later be excavated in tattered strips by late nineteenth and early twentieth century archaeologists, beginning the painstaking process of piecing what little might remain of those texts back together…:

Scribes are the unsung heroes of the survival of any classical work; without them there would be no written papyrus texts and codices, and hence no fragments of drama or poetry. We know that scribes often worked from ‘scriptoriums’, maybe booths or workshops in city marketplaces where customers might request a work to be copied for their private libraries.

Scribes are the unsung heroes of the survival of any classical work; without them there would be no written papyrus texts and codices, and hence no fragments of drama or poetry. We know that scribes often worked from ‘scriptoriums’, maybe booths or workshops in city marketplaces where customers might request a work to be copied for their private libraries.

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century

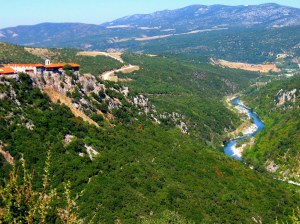

In 1959, a previously unknown edition of the ninth century  Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post

Photius’ Lexicon is not alone in surviving in the library of a Greek monastery; many works were taken to such safe places following political and religious upheavals in the east, for example after the sack of Constantinople by western soldiers during the so-called Fourth Crusade in 1204, as explored in an earlier post  Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews.

Photius I (later St Photius the Great) was a secular clerk who was appointed Patriarch (or Pope) of Byzantium in 858 following a time of often bloody religious schism in the city between the iconclasts, who wanted to destroy images of God as idolatrous, and the orthodox church, which viewed such depictions as holy relics. In 868 Photius was temporarily unseated but returned to the patriarchal throne in 877 when he continued his persecution of the city’s Jews.